For anyone with Imposter Syndrome, read this.

There’s a persistent voice that follows many people who care deeply about their work. It doesn’t yell. It whispers.

You don’t really belong here, do you?

This is the voice of imposter syndrome. And it doesn’t just live in our minds, it lives in our bodies, in our creative blocks, in the hesitation before we hit “publish.” It shows up in labs, in lecture halls, in studios, in strategy meetings. It thrives in places where expectations are high and perfection is the norm.

Most of us think this is just nerves. Or humility. Or a sign that we need to work harder. But it’s more than that. It’s a patterned response to complex conditions. It’s layers of personal, cultural and systemic influences on our behavior. And if it’s never examined it will shape our careers, for better or worse.

This entry is a reflection on what it means to carry this voice. What it takes to shift our relationship with it. To understand the (often invisible) mechanics of feeling like a fraud, even when there’s proof you’re not.

If any part of you has questioned whether you’re “legit enough” to do the work you care most about, keep reading.

It starts with scripts and stories

Imposter syndrome doesn’t start the moment you enter a meeting or open your laptop. It begins much earlier in life, quietly and subtly, through patterns we inherit from our environment.

Many people who struggle with self-doubt weren’t raised in environments where their sense of worth was unconditional. Instead, we learned early on that approval is earned. Sometimes through being good and smart, sometimes by being talented or agreeable. Through not making mistakes. Through meeting expectations, whether they were outspoken or silently enforced.

I too grew up in an environment where these expectations were always present. I was supposed to “get it right.” To try my best, constantly. Sentences I heard over and over, like: “Are you this stupid?”, “Why don’t you get this?” or “Why are you doing that? Why aren’t you doing it like it’s supposed to?”.

These are the scripts we don’t realize we’ve memorized. Scripts we now use to filter the information we receive from the world.

You might have learned that praise follows from perfection, not process. That confidence is for people who “know what they’re doing.” That speaking up should only happen when you’re sure. And that needing help means you’ve already failed.

Later, in school or work settings, these beliefs start blending with additional layers of our environment. We learn to read social cues and feel cultural pressures. Suddenly, not knowing something becomes a threat to the way our friends or peers look at us. Asking questions feels risky: “what will they think of me?”. And even when you do achieve something, it doesn’t feel like it’s yours. It’s just something you had to go through, you were “expected” to do this anyway.

I’m not good enough

What’s difficult is that this feeling often coexists with a drive to do good work. Because you do care about your work. You do prepare. You want to make something thoughtful, useful and meaningful. You want to have an impact. But underneath that effort, there’s often a quiet calculation of which we’re not even aware: will this be enough to prove I deserve to be here?

Our environments often rewards the external signs of confidence more than the internal process of learning. If you tend to think deeply, question yourself, or prefer observing before acting (like I do), you can feel out of sync with cultures that expect constant certainty.

In academic or professional settings competition is high and feedback is minimal. The same is true in the creator world, where comparison is constant and the performance of your work is more more visible than the real work behind your content (”how many views did you get?” vs “what was that video about?”).

What I find most interesting is how common it is, especially among those who actually have something to say.

Some of the most thoughtful, capable people you’ll ever meet carry this feeling. People with advanced degrees. People who lead organizations. People creating meaningful change. They’ve built systems of overworking, overpreparing, overperforming. Anything they could do, internally, to silence the doubt.

But it doesn’t go away. It just gets quieter for a while, until the next stretch, the next challenge, the next new room. And in those moments, the old scripts come back. What if they realize I don’t really belong here? What if I only got this opportunity because someone made a mistake?

What if I’m not good enough?

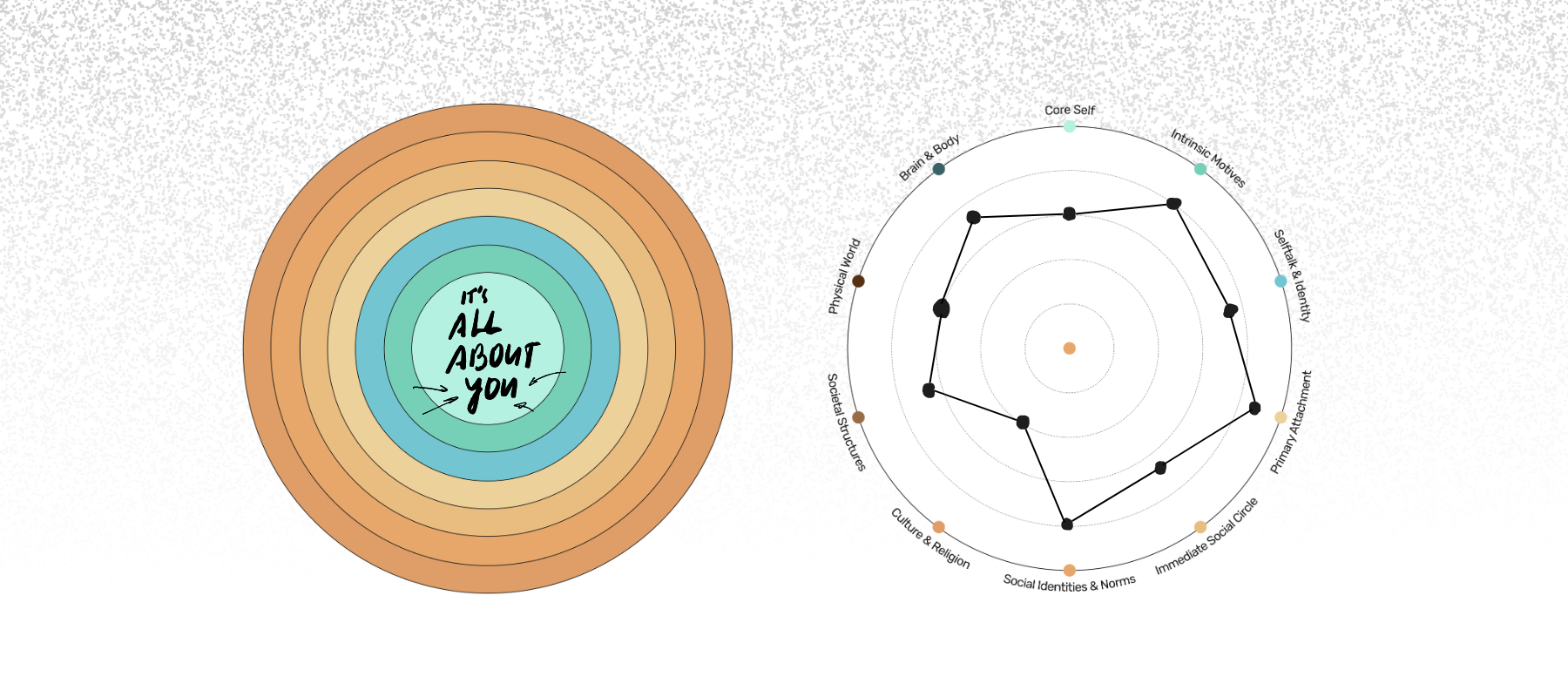

Layers on layers

Like I already hinted at, Imposter syndrome doesn’t emerge in the vacuum of a household or family system. It’s a byproduct of the environments that we live in.

These patterns and behaviors are layered in our subconscious after years of exposure to:

The societal structures around us

The physical environment we live in

The culture we’re part of

Our religion or belief system

Social identities and norms we grew up with and belong to now

Our immediate social circles (partner, close friends,..)

The primary attachments, our care takers

Our inner dialogue and the labels we give ourselves

So much more…

Personally, I’ve often felt like my style of thinking, my breadth of interests, my more emotionally attuned way of showing up, didn’t quite “fit” the expected mold of how a scientist or creator should operate. But when you grow up with the praise for doing things “right” (at home, at family gatherings, in school, in academia) it clashes with your reality. You feel like your natural way of thinking isn’t the right way at all.

It makes you question everything. Not just your work. But your identity. Your worth. Your belonging. So what do we do with all of this information?

First, we call it out for what it really is, a pattern. Not of personal failure, but as societal inheritance. And then comes the work of dissecting these layers, one by one. In other fields, like psychology, this is also known as “shadow work”. We try to observe which scripts are actually ours, and which ones we’ve been carrying for so long, we forgot to question them.

One of the most powerful shifts, personally, came from a simple question I started asking myself:

“Where does my environment end, and where do I begin?”

Which expectations are truly mine? Which values do I actually want to live by? What happens when I stop trying to earn belonging, but start claiming it instead?

How do we start healing?

There’s a point in the imposter syndrome cycle where you stop questioning if you feel it and start asking how to function with it. You get tired of fighting the inner critic, so you start working around it.

Often, that means coping. And for some of us, it has become second nature.

You learn to manage the self-doubt by becoming extremely prepared. You double check your facts. You triple check your phrasing. You take one more course, read one more book, revise your paper (or e-book in my case) one more time. Just to quiet that part of yourself that says, “You’re not enough.”

And the amazing thing is: at first it works! The perfectionism becomes a kind of armor. The overworking becomes proof: Look how hard I try, now they do have to take me seriously. The imposter voice becomes manageable. As long as you don’t stop moving, that is.

But that’s a trap for many of us, “imposters”.

In hindsight, I can see how exhausting that was. Not just the work itself, but the emotional labor of constantly trying to stay one step ahead of the feeling. It’s like running from your own shadow. Even when all that looks like growth from the outside (career moves, highly produced content, academic recognition,…) at a certain point the mental load becomes too much.

You end up building a version of yourself that needs to perform at all costs. And the cost is real. Creativity and connection with others starts to feel heavy. There’s not a lot of mental capacity free for anything else. Rest and fun becomes something you have to earn, not something you deserve.

And so we feed the paradox: the more we run away from these feelings, the more disconnected we become from ourselves. And the more disconnected we are, the more imposter syndrome thrives.

Honesty as an antidote

Eventually, you realize: the problem isn’t the voice that says you’re not enough. The problem is believing that voice is telling the truth. Healing, then, isn’t about silencing that voice forever. It’s about shifting your relationship to it. Recognizing when it’s old programming.

We go through the motion of feeling. Because, as my psychologist friends have told me again and again, understanding impostor syndrome cognitively (knowing the cycles and seeing the patterns) isn’t enough. Knowing alone won’t change the response your body learned over years of repetition.

The real work, the therapeutic work, happens when you sit with those uncomfortable feelings in real time. It happens when you notice the tightness in your chest, the flush of shame, or the familiar urge to hide. You pause there, in that discomfort, and instead of retreating to safety, you hold space for curiosity:

What is this feeling protecting me from?

Whose voice does this sound like?

Why am I feeling this way right now?

What am I afraid will happen?

Where did I learn this response?

In therapy, this means creating a safe, regulated space where these feelings can surface without judgment. To slow down and notice your physical and emotional reactions in the moment.

A therapist might gently guide you into staying with discomfort instead of immediately trying to fix it. They help you unpack the underlying fears or narratives we talked about, identify whose voice you’re hearing and practice responding differently.

The therapist’s presence helps you regulate these emotions long enough to rewrite how your body responds to familiar triggers. Over time, some of what used to be automatic begins to loosen its grip, making space for new, healthier responses.

For me, the turning point wasn’t dramatic. I wish I could tell you something new and groundbreaking. It was gradual. A slow, unglamorous series of moments and conversations with friends where I realized I no longer wanted to spend my life chasing “enoughness” for other people. I’m still on that journey, and therapy is where I’m also looking into next. I want to work from a place where I am okay with myself, whatever the standards of others.

From fear to authenticity

Most people with imposter syndrome are not egotistical. Quite the opposite. They’re self-aware, reflective, even cautious. But that caution can (and for many of us, has) become a cycle of comparison and correction, where we’re always trying to close a gap between who we are and who we think we need to be.

But who set that benchmark?

Was it a role model you admire? A supervisor who expected too much? The algorithm that rewards performative confidence? A system that praises confidence over authenticity? Which layer or pattern do you think it was? When you pause and trace the origin of your self-doubt, you often find that the standards weren’t yours to begin with.

There’s a difference between asking yourself “Am I good enough?” and choosing to define what “good” even means for yourself. This is the shift we need.

What we need to do is move from externally defined narratives to internally chosen ones. So we get back to the drawing board and ask ourselves the question: “What kind of creator, scientist, communicator (or simply what kind of human) do we want to be?”.

This is where self-authorship and your authenticity begins. You stop asking: “How do I prove myself to them?”. And start asking: “What matters to me? What kind of work do I want to make? Who do I want to reach, and why?”.

You’re building a new internal reference point. One that’s rooted in values, not validation. One that allows for imperfection and makes space for growth.

The shift

That shift can be scary at first. When your whole sense of security has been built on performance, “dropping the act” can feel like exposure. But it was also one of the most stabilizing things I’ve done. Shame thrives in secrecy. It feeds on silence and perfectionism. When you name it, when you tell the truth of your experience, it starts to lose its grip.

The more honest I become about my own relationship with imposter syndrome, the more other people open up about theirs. Not just friends or peers, but also my mentors and role models. People whose work I deeply respect. People who, from the outside, look like they had it all together.

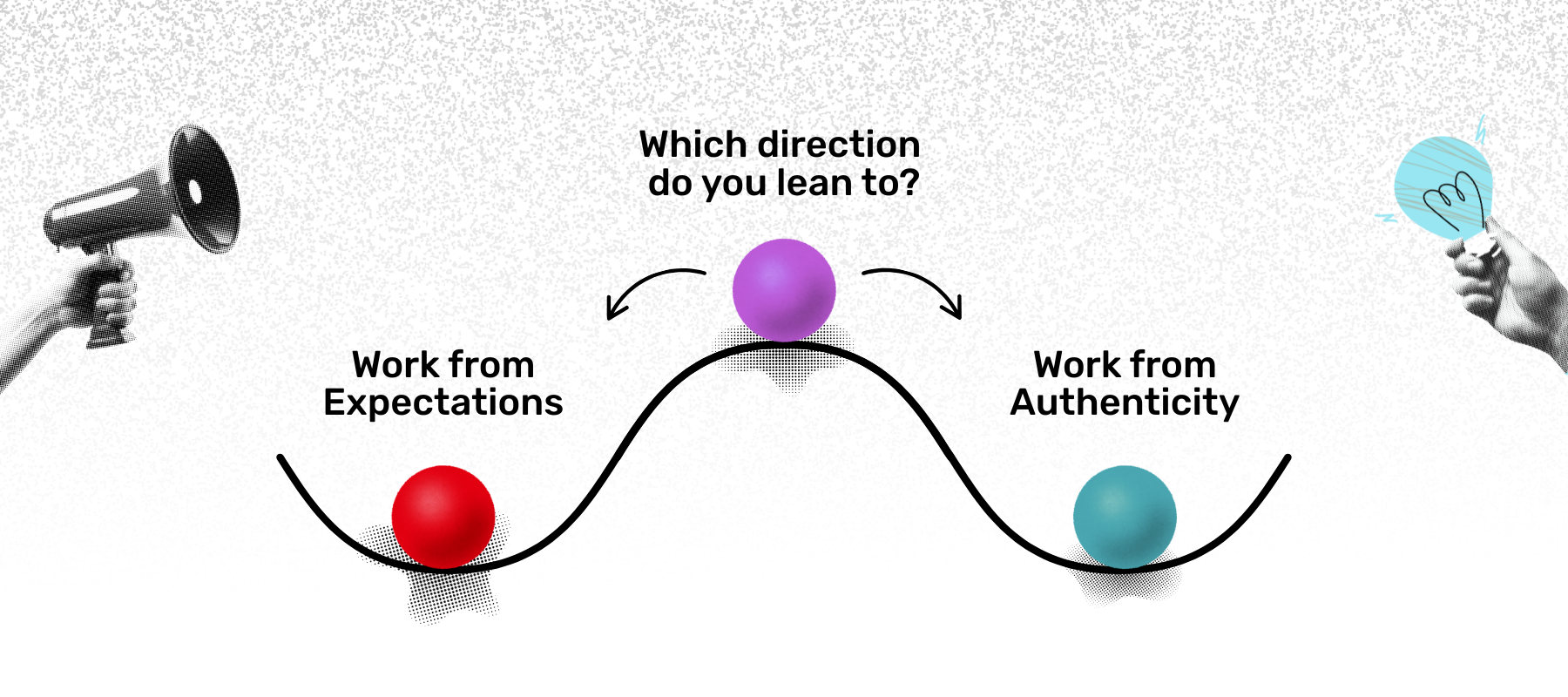

I started thinking about this as a concept of alternative states (biologists will recognize this term):

On one side is the familiar story: do more, be more, prove more. You take on the world’s expectations. You work from outward > inward. The environment dictates your identity.

On the other side is authorship: a self built not from credentials but from curiosity. You work from inward > outward. Your identity informs your environment how you present yourself to the world.

The space in between is scary… and so, so, vulnerable. It’s where the old story is loosening, but the new one hasn’t fully taken root. Some days, you lean to the left and are back in the world of expectations. But if you can stand in that space, even shakily, something begins to change. Step by step, you lean more towards the right, to authenticity. You start trusting your instincts again. You stop waiting for permission.

And your work begins to feel like it belongs to you. Not to the version of you that’s trying to impress someone else. This doesn’t mean imposter syndrome disappears. But it does lose its authority. It becomes just one voice in the room, not the one holding the mic.

Tools for your toolkit

Okay, I said this wasn’t going to be a “how to” piece (it still isn’t), but that doesn’t mean I can’t share a few tools that helped me along the way! These small tools, questions and practices gave me just enough space to see things differently. I still use these today.

1. The observational space

This one practice changed everything. The simple act of noticing. When you feel a moment of imposter syndrome coming up, you can start looking at it from this calm, warm curiosity (credits for that go to Emily Nagoski). Just witness it. Think to yourself, what is this feeling trying to protect me from?

That’s the thing about imposter syndrome: it often comes dressed as self-criticism, but underneath, it’s usually fear. Fear of rejection. Fear of being misunderstood. Fear of not living up to the version of ourselves we’re trying so hard to be. It’s giving you the clues you need to understand your own layers of influence.

2. Journaling as dialogue

This one isn’t new or profound. But therein lies the proof of its value as well. Journalling has been working for people as long as we can read. Not journaling in the “dear diary” kind of way, but as some internal debugging. I’d write out the thought loops (the fears and shoulds), and then start answering them. In looking at: where do my patterns show up? And, where can I make a decision based on my values?

Often, just putting the words on paper helps. When fears live only in your head, it feels huge. When you write it down, it feels smaller. I could see how certain situations reliably triggered old scripts: public speaking, writing on topics I cared deeply about, moments where I had to “claim” space. And with that clarity came the possibility of choosing a different response.

3. 80% is enough

One of the most practical shifts I made was adopting a principle that creative people know well: the 80% rule. 80% done and publishes is better than 100% and never finished.

For most of my life, if something wasn’t complete and DONE, I’d keep working on it. Or I’d scrap it entirely. And the beautiful irony? The things I was most afraid would be “not good enough” were often the ones that resonated the most.

4. Internal validation

Yes, I still chase external markers to feel like I am doing okay: recognition, feedback, credentials, the right collaborators. But I’m trying to be different about it. When a moment like this comes, I get back in my observational space and try to ask myself: What would it look like to trust my own barometer of “enoughness”?

I’m slowly trying to define my success by aligning with my values, not if I get an applause from the world. It also means grieving the version of myself that has spent so long trying to be acceptable. Which is hard, to sit in that feeling. But also freeing, afterwards. Memory by memory. And slowly, consciously, I am choosing to build a self I trust… even when things get hard.

5. Conversations that can go deeper

No tool has helped me more than talking with people who’ve been through it too. Not surface talk. But straight into the depths. The kind of conversations where someone says, “Yeah, I’ve felt that exact thing.” Where they don’t try to fix you, but just hold space and the occasional mirror.

I wouldn’t have been writing this entry without the long talks with Eline, Jolien, Valentin, Dagmar, Inti and Charlotte. Find your peeps, work through it in community.

Some of those conversations can happen in therapy. Others with close friends or collaborators. So if that is something you feel you need, go for it! The stories we carry privately often lose their power when spoken aloud.

Now you

When you’re in the thick of it, it can feel like imposter syndrome is all there is. But these tools, however small, open the door. An open door where light can get in.

There’s a version of you on the other side of the doubt. One that doesn’t need to prove your worth to exist. One that can take up space, not because you’ve earned it, but because you are.

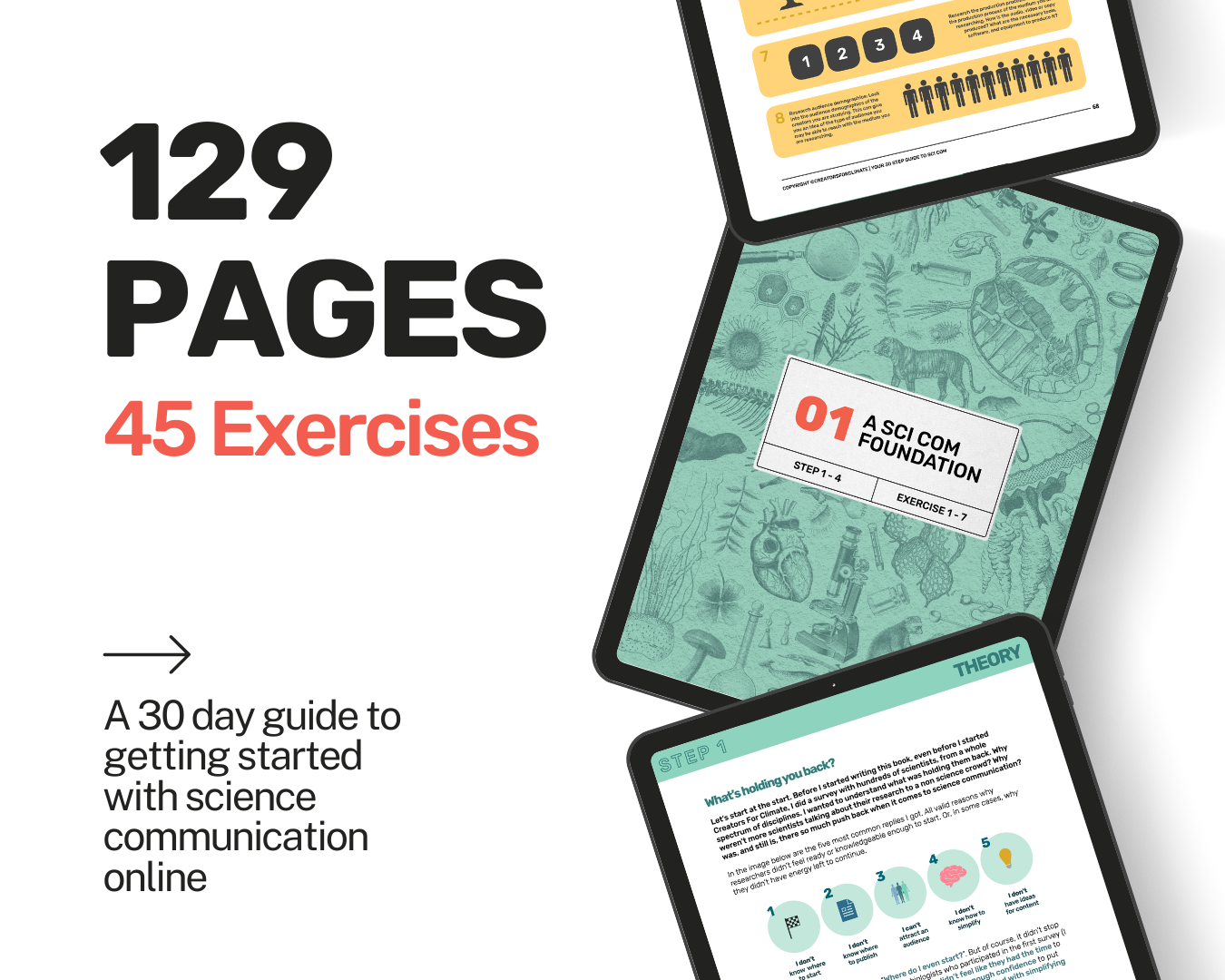

Want to start with science communication?

Latest blog posts